Although some time has passed since my last video, this one picks up right where the journey left off. Since being back in Hawai‘i, I’ve been balancing different projects alongside housework as I prepare to return to Aotearoa next week. It’s summer here, which means the days are longer and so much more can be accomplished.

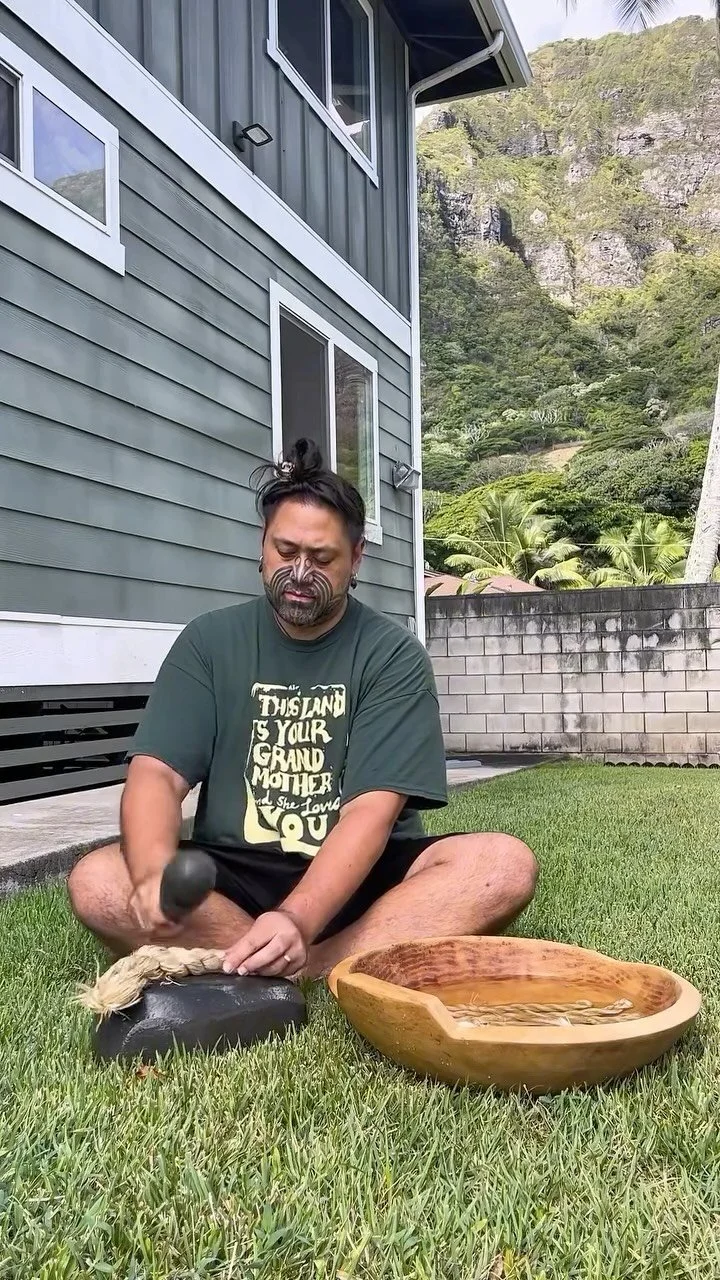

Here I’m preparing the muka gathered during my last trip home. This muka will be used to weave a maro (loin covering), which will sit inside the maro-style piupiu I’ve been working on.

Today, most woven garments don’t require much fibre softening since they’re worn over modern clothing. But in the past, when woven garments were everyday wear, the fibres were softened extensively so they would be both warm and comfortable.

In my last video, I left off at the stage of extracting muka from the harakeke leaves. Many people move straight into twisting the fibres immediately after the hāro (scraping), but because my harvesting time is limited, I dedicate all of it to gathering and extracting. The challenge is that when muka is left untwisted, it can easily tangle and turn into a mess—so handling it takes practice. Another difference is that twisting straight after the hāro means the muka is moist, making it softer on the skin and more traction on the thigh. Twisting dry muka is rougher and has no traction, but with Hawai‘i’s humidity keeping the skin slightly dewy, I find it works well. That’s why I do the miro (twisting) outside in the heat and humidity. I like to joke that my biggest flex is being able to miro without pulling out my leg hairs.

Once the miro is done, whenu are gathered into a kōrino, or hank. Each kōrino is made up of different lengths of whenu. If you look back a few videos, you’ll see where we separated the leaf strips into lengths—those same bundles are now hanks.

Continued in comments below⬇️

My final hours are always a whirlwind — trying to squeeze in as much as I can before tossing everything into my bags and rushing to the airport. I spent my last morning preparing muka and tidying up the workspace so it’s ready for when I return. It’s been a full-on month, and yet I often forget just how much I’ve done until I pause to reflect. I’ve harvested everything that could be taken from the pā and will now give it a good 2–3 months for the fours and fives to come through. My mind’s already there, imagining how they’ll be used. Time will fly — it always does — and before long, I’ll be back again.

It’s been a really good trip, but I’m also happy to be home.

Since arriving, I’ve been feeling a little under the weather, so I’ve taken the liberty to rest — bags still unpacked. It’s wild to think that one moment I’m in the depths of winter, and the next I’m in the heat of summer, switching from driving on the left to the right. It always takes me a little while to truly reflect on the trip, settle back in, and prepare for the long list of to-dos waiting for me.

This time of year is when I give the house and yard a proper clean — pressure washing the concrete, scrubbing rugs and floors, cleaning windows inside and out, clearing storage spaces, reorganizing, planting. I genuinely enjoy it, and somehow it comes around faster every year. It’s easy for housework to pile up like a great big wall, so I try to stay ahead of it and this is my time to get it done.

Oh yes and with that Im planning to get in some much needed daily beach time!

It looks lonely, but I am not alone.

It looks boring, but I am never bored.

It looks like a lot of work — and it is — but it’s worth every moment.

This is where I feel most present.

Every whakapā, every hākuku, every miro — an echo, a remembering, a knowing, a living.

The work might seem repetitive from the outside, but within it lies so much more.

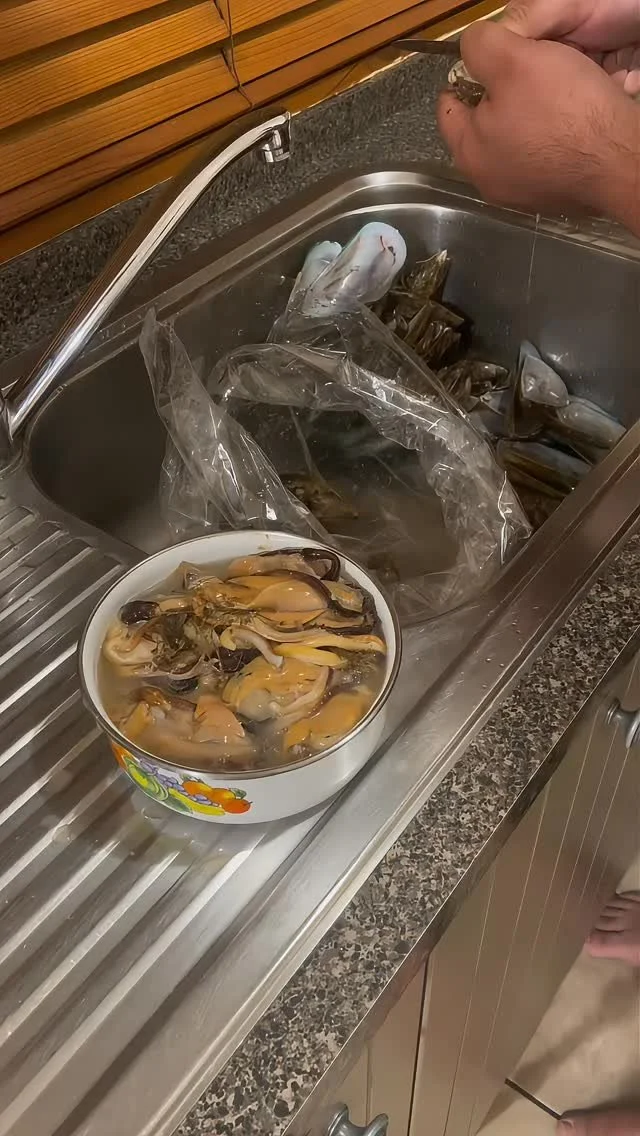

When I left wānanga last week, I was gifted a bag of mussel shells. I brought them back to the motel, quickly shelled the mussels, made myself a warm soup for dinner, and cleaned the shells as best I could so they wouldn’t stink up my bag on the return trip to Tūranga. After rinsing them, I laid them out under the patio—it was rainy and windy, so I tucked them into a sheltered spot and prepped some ziplock bags for the morning.

I woke early, packed them up, and dropped half off to @_manu20_ on my way to the airport. Once I got back to Muriwai, I found a little corner in the garden to store the rest. If I hadn’t been flying, I wouldn’t have needed to clean them at all—I would’ve just buried them. The soil and all its unseen life would clean and harden the shells over time, and when you need one, you just dig it up. If you do this, you’ll always have a stash of mākoi on hand. You’ll never be without. I just have to make sure I bury them when the kids aren’t watching—otherwise, guaranteed, they’ll be out there digging them up!

I believe these are farmed mussels, these are a very good size. Wild mussels however develope a thicker shell and are stronger but I tested these and they are pretty good. When you learn how to handle a shell and build experience using them then you can peretty much use any shell, it will just have a shorter lifespan.

I caught a bit of a chill over the weekend, so I’ve been taking some much-needed rest and time to warm up. Yesterday, I started feeling better and did a bit of prep work for the week ahead. It was a beautiful day for it. I love that time of day when the evening sun pours through the window, casting its golden warmth across the shed. It’s those quiet, glowing moments that carry me.

One thing about piupiu making is that at every stage of the process, the strands are at risk of damage—and with one wrong move, all your hard work can be undone. There’s no shortcut to learning this craft. You have to make mistakes to truly understand the qualities of the harakeke and how it wants to be handled. From the outside, it might look like we’re working with something strong and indestructible, but the truth is, these strands are incredibly delicate. They can split easily and, once that happens, they’re unusable.

Before heading away for the weekend, I managed to finish a few bundles of pōkinikini. I boiled them and hung them to dry, thinking the cold weather would slow down the curling process. We affectionately nicknamed this stage “babysitting” because the strands need regular attention to stop them from curling into one another. After boiling, the leafy parts become soft and leathery—this is when they’re at their most pliable, and easiest to separate if they start to twist together.

But I left mine without a babysitter—and when I returned, they had curled tightly around each other. The window of pliability had passed. So, here’s what I did: I soaked the strands for about 15–20 minutes—no longer, to avoid water marks—to bring back their flexibility. Then I rehung them and slowly worked through each strand, one by one, to separate them. I prefer to start from the bottom and work my way up.

Ideally, you never want to get to this point. But life happens, and it’s important to know how to recover when it does.

After the toetoe, which is the process of breaking the leaf into strips, I bundle the whenu into groups of twenties, tie them securely and then place them into water. This just keeps the whenu fresh, and when Im ready to do the whakapā I take it out and stand it up until the excess water has shed then start the whakapā. The whakapā or scoring is a very important and tedious part of the process. Any mis-cut can cause a whenu to be wasted. There is a very thin margin for error on the whakapā. The scorer can tell if a cut is good or not by just looking at the cuts. The cuts are presses open and then the hākuku is done. The hākuku is difficult to master. Between the two hands there are alot of mechanics happening all at once. Building strength as well as finesse in the hands is important. While there is alot of strength needed for the scraping, the hands must also be gentle. So finding that balance takes time and practice. Once the hākuku is done, two pōkinikini are joined and plied together on the leg forming a pair. Slowly the pairs are stacking up. I always have this visual image of nibbling away at the mahi meaning, alot can be accomplished if everyday you take a few nibbles at the work, little by little, it will add up very quickly.

It’s been beautiful weather here in Te Tairāwhiti, perfect for slowly chipping away at the piupiu. Working with a new pattern means drafting new boards for marking. This particular pattern uses three boards—two with a wider width and one thinner. I’ve seen boards made in all sorts of ways, but I find wood glue to be simple, strong, and effective. If I’m making a large number of piupiu, I prefer to use hardwood. Pine boards wear down quickly and can develop little potholes. These pōkinikini will be 28 inches in length, so I’ve made sure my boards are long enough to carry the full pattern.

Last month I cleaned out the pā, as some of you may remember. Now, a month later, what I call my “fours” are ready. The “fours” refer to the prime leaves. We never cut the inner three shoots—the awhirito and the rito—but anything outside of that can be harvested. The fourth leaf is soft, pliable, and free of blemishes, making it ideal for weaving.

When harvesting from an overgrown pā, the leaves tend to harden and become scarred or blemished from being battered by the wind and other elements.

When bundling leaves, they should be bound tightly around the take (stalk). Tying too high on the kauru (leaf) risks cracking the leaves, rendering them unusable. There’s a great deal of care that goes into preparing the leaves so the pōkinikini come out as best as they can—the more they’re handled, the more they’ll look handled.

Everything comes back to the pā and how it’s cared for. Over the next two weeks, I’ll be focusing on removing the scale insects that have settled in. The corrugated sheets along the fence were originally placed to keep the chickens from getting out, but they’ve created a safe haven for scale. I’m looking forward to making time to clean it all out.

It’s been so warm here in Te Tairāwhiti, and I’ve really enjoyed being out in the sunshine getting my mahi done. I started this piupiu a month ago during my last visit, and it has since dried beautifully—perfectly ready for weaving.

This piece is for my mate Parekura, who is a taura of Te Kura o Tūranga, a wānanga mau rākau based here in Tūranga-nui-ā-Kiwa. Kākahu (traditional clothing) are a vital part of a toa’s ability to carry out mātataki (ceremonial protocols). Without the appropriate kākahu, those kawa cannot be fulfilled. So the role of these garments is not just aesthetic—they hold significance in honouring the ceremony itself.

There are also practical functions that certain kākahu provide for kairākau: freedom of movement, protection, warmth, concealment of weapons, shelter, camouflage, and more.

When it comes to weaving, I think I’ve mentioned before how much I enjoy being outside whenever I can. A lot of the weaving we do tends to keep us indoors, sitting in one place for long stretches. So whenever there’s a chance to be outside, I take it.

I’ve set up a space next to the pā harakeke where I plant my turuturu (weaving sticks) directly into the ground to hang the piupiu. This is how our old people used to weave. I like the sticks to be taller so that I can work between a standing and seated position—I prefer to be standing, but it’s nice to have the option to sit as well. When it rains, I move to the shed, where I have a place to hang the piupiu.

One of the things I love about our weaving is how portable it is. We don’t rely on looms or heavy tools that tie us to one spot—our methods allow us to move, to work where we feel most connected.

There are still a few elements I want to add to the piupiu—some details on the tātua—which I’ll do once it’s dry. I’ll be taking it back to Tūrangi with me in the morning to continue working on it while I’m there for another kaupapa over the weekend. I’ll return to Tūranga on Monday.

Continued in comments ⬇️

It’s been a privilege to share Punarua with our iwi of Tūwharetoa this Matariki. Commissioned by the 2024 Biennale of Sydney under the theme Ten Thousand Suns, Punarua pays tribute to our esteemed rangatira Koro Te Kanawa Pitiroi, who played a pivotal role in preserving the oral traditions of our iwi. One kōrero in particular, Māui-takitaki-o-te-rā, became the guiding narrative in the creation of this work.

Punarua was woven in Tokaanu by Tūwharetoa weavers Hone Bailey, Paehoro Konui, Merānia Heke-Chase, and Manu Fox. Over 1,800 harakeke leaves—primarily sourced from Awahou (Foxton)—were used, and the piece was dyed using traditional methods with mānuka, paru, and raurēkau. Taking more than 1,000 hours to complete over two and a half months, the work stands 207 cm tall and 182 cm in width.

The exhibition also features a short documentary that follows the full journey—from harvesting the fibres to its international debut—offering a glimpse behind the scenes and into the heart of the kaupapa.

This Matariki, we celebrate the threads that connect us across generations. Punarua will remain on long-term loan at Taupō Museum for the next two years, giving whānau and community the opportunity to visit, learn, and reconnect.

We’re deeply grateful to Taupō Museum and curator Piata Winitana-Murray for helping make this exhibition possible. It was incredibly important to us that Punarua return to Tūwharetoa, and we’re so thankful to see that vision realised.